(A grateful son remembers)

A Looming Poetic Presence

The Word Is an Egg, my 11th book of poems, carries the following dedication in its opening pages:

To:

Fasimia, my mother,

Indigo fingers

Weaver of fabrics and fables;

Iya Onisuuru:

Indeed, “The patient eye will see the nose” ,

while the acknowledgement in The Universe in the University, my 2005 University of Ibadan valedictory lecture, registers my gratitude to “my mother, Fasimia, Iya Onisuuru, compassionate like a water lily, weaver of fabrics and fables” who [together with my father], “taught me the value of hard work and integrity, and made me aware that Character Is Beauty: Uwa l’ewa”. Gracefully enough, Mama was present at that lecture.

‘Human in Every Sense’, the third movement of Midlife, a book considered by many as the most autobiographical of all my works, has sections rippling with Mama’s native wisdom:

‘See with your whole body’, my mother said

your whole body

Ponder the silence of the noise,

the noise of every silence

the bitterness of honey

the lacerating coldness of the sun

Ponder the thirty-year old pounded yam

which still burns the flippant finger’

And when in August 2005, Hurricane Katrina struck in New Orleans, destroyed my books and manuscripts and everything my family owned, and came so close to killing my wife and me, Mama appeared to me in a dream with words of consolation and comfort. This was at the Red Cross Refugee Center in Birmingham, Alabama, USA, seven days after the hurricane. (Miraculously enough, at the time of this dream encounter, Mama was in Nigeria, completely unaware of her son’s close shave with death by water). Evoking my historical and spiritual provenance, Mother said with a near-oracular authority: the Spirit of Water (Osun) gave you to me; the flood of another land will not take you away. ‘What Mother Said’, the poem whose narrative looms over the entire volume, is the longest and most deeply indigenous in City Without People: The Katrina Poems.

My journey to poethood is marked by luck and salutary serendipity. With a father so deep with words and so friendly with the drum, and a cloth-weaver mother who serenaded the loom as she steered the shuttle through a phalanx of threads, Fortune placed me in a household where sound matters when it is accompanied by sense; a place where music earns its resonance from its moral force.

Iya Onisuuru: Uwa l’ewa (Paragon of Patience: Character Is Beauty)

Mother never spoke unless – and until – it was absolutely necessary. She was a woman who thought about things. And she thought long and deep. And so when she spoke, she never missed the mark. Quite often she predicted future happenings with a near-prophetic accuracy, a habit which showed me early in life that you could only ignore Mama’s warning at your own peril. Look before you leap; think before you talk, she was fond of saying. See with your body, your whole body: two eyes are not enough. In my days of youthful exuberance, I used to consider her too quiet, too slow, too uncomplaining, too accommodating. Now, I know better.

This meditative, philosophical disposition was prelude to another remarkable virtue of Mama’s: tolerance and the necessity, even indispensability, of difference. If God wanted all of us to be the same, she used to tell me in my childhood days, he would have created us all with the same language, the same colour, the same face, the same height, the same manner, the same taste, the same smell, the same strength, the same weakness. Our strength is in our difference. . … With that archetypal Yoruba saying, Oju orun tugba eye fifo lari mora kan ra (The sky is wide enough for numerous birds to fly without colliding), Mama taught me from very early in life the communal, liberal, live-and-let-live principle which informed her relationship with other people. I remember now with gratitude and appreciation her daily invocation which usually came at dawn, specifically after the second cock-crow. With the tip of her middle finger stroking the earth, she intoned the following:

Oju mo loni The day has broken

Ko loo mo o Time for every tradesman to pick up their trade

Oranu ma keke The cotton-spindler has picked up the spindle

Uwo Abaye Barisa You God in Heaven

Ki mo ba tii ke a ri komonikeji mi loni Whatever I wish for my fellow man today

Baa li ko je ri komi Let it be exactly that way for me

I was too young in those days to apprehend the full weight of this invocation: the inu mimo (clean inside/soul), Inu ire (Wholesome/healthy inside/spirit) that must have led to it, the confluence of confident morality and deep spirituality that must have warranted its pronouncement. For, in the case of some people, that kind of prayer would have amounted to a frightening self-curse or self-indictment!

A proud, evil-shunning, community-spirited person, Mother hated all lying and pretence. No craven masks. No humbug. Gba mi ko ti ri mi (Take/Accept me as I am), she often said. Though we were people of modest means whose meals frequently went without meat, whose wardrobe hardly boasted more than two pieces of functional clothing, Mother taught her children to avoid oju kokoro(greed), ou/ulara (envy, jealousy, covetousness). She saw poverty as a curable disease, and hard work, diligence, and conscientiousness as the healing pills. Good character stood at the top of it all, for wherever it is, integrity and success are bound to follow.

I remember now, that incident in December 1959, my final year at St. Luke’s Primary School, Uro, Ukere. In addition to being Best Student in academics, I was also star actor in the end-of-year school drama, the one that was chosen to lead both the opening and closing glees. For this special assignment, I needed a white singlet top upon an attractive piece of cloth to cover my body from the waistline to the toes. Mother’s lean wardrobe had only one piece of wrapper fit for the purpose, and I was reluctant to borrow it for my school drama with all the possibility of returning it after the event, soiled and defaced by the notorious December dust. An acutely intelligent woman, Mother read my mind, divined my need, and surrendered the only pretty piece of fabric at the bottom of her box. In response to my mild and grateful protest, Mother said ‘Gba ko yaa mu sire re. Ki mo ba ti mo ku, mo ti a l’egberun eu, mo tia l’atabatubu aso (Take this away and use it for your drama. If I do not die young, I will still be the owner of countless clothes). This wrapper added much grace and colour to my performance. I felt the warmth and spirit of my mother in every movement. The hopeful resonance of her words enlivened my singing, gave me a place in the future. Incidentally (and ironically), the legend imprinted on this piece of fabric by its makers is OMO ERIN NI I JOGUN OLA (The elephant’s offspring is the inheritor of abundant wealth). Mother was no physical elephant; for she was petite and beautifully so, but she possessed a conscientiousness, stubborn commitment to the right and just, that made her a moral giant.

Just one more episode that speaks volumes about Mama’s unwavering integrity. On my way back from school one hot and hungry afternoon in 1957, as I passed through Oja Oba in Atiba, I found, on the main road, a kobo (one penny). Upon getting home, I announced to my mother with triumphant enthusiasm: Mama, i yi kobo ki mo ri lale (Mother, here is the kobo I found on the ground), whereupon my mother grabbed my left ear and twisted it until my painful scream nearly brought down the roof. “Ale i so o; ona i so’fa; uran mi i s’ameo eleo sola. Kiakia, sa pada s’Atiba ko da kobo o pada sibi koo ti ri”. (Money never grows on the ground; boons never sprout on the road. I do not come from the stock that fattens on other people’s money. Run fast back to the place where you picked up this kobo from the ground and return it to the road). Of course, I knew there would be no lunch for me until Mother’s order had been meticulously carried out. I ran back and flicked the kobo back to the dust where I found it about two hours before. I went back home, penniless, but richer than all the kings in the world.

These and other instances attest eloquently to Mother’s moral force and stubborn integrity. Humanity was right in the centre of her moral philosophy. Eo fun ruru, e toniyan, (Money looks attractive, but it is never as important as the human being), she often said. Oniyan l’oye (The human being is the supreme royalty). Ubi i ye ibikibi ko baa gbee si (The seed of evil will never sprout well, no matter where you plant it). Mother never based her regard on what you had, but what you were. Her premium, always, was on your character, not your cash. Throughout my life as a working adult, Mother never harassed me with any impossible demand. She accepted whatever I was able to offer and rewarded me with prayers and rousing verses of my oriki. Just like my father too, she took pride in my creative and academic achievements in her typical humble, unobtrusive, non-triumphalist manner. At the end of virtually every visit, when I was ready and set to leave her, Mother usually intoned in prayerful counsel: I jare, momo ba an huwa ibaje o. Ayeti lu jara bi kobo Oyibo. Oko ujoba a koo lose o. (Please do not join others in acts of corruption/misconduct. The world is perforated like the white man’s penny. May you never fall into the government’s trap).

Mother possessed more than an ordinary share of oju minin (compassion, mercy, fellow feeling, a sympathy which deepens into empathy), an expression which featured so frequently in her daily vocabulary, and whose humane import informed her social and moral interactions. Oju ni i roju i sainu (It is a vital part of our humanity to show mercy to one another), she often said. Her social and economic ‘ideology’ is summed up in yet another of her frequent sayings: Erun kan i je ke run kan a o (One mouth must not do all the eating while the other mouths merely watch). K’otun je, k’osi je, ni male i dun (The right has something to eat, the left as something to eat, that is the only way the land can be enjoyable). Fairness, equity, even-handedness: these were all active chapters in Mother’s book of interpersonal relationship – ideals which take me forcibly back to that dawn invocation encountered in the opening part of this tribute. As I often quip, my first lessons in the theory and praxis of social justice came from the household which nurtured my childhood. Mother taught the first half of those lessons; Father the taught second. Together, they gave me a treasure that money can never buy. This, without doubt, is the provenance of my socialist-humanist perspective on life.

But Mother was no angel. Her words of reproach (which came not too often) could be lacerating and acidic. I saw her get angry a couple of times, and she never baulked at a passionate defence of what was right and fervent excoriation of what was evil. Arinumobi baba ode; arinumobi agba ika (A person incapable of anger is the dean of fools; a person never angry at evil is the king of the wicked), she said one morning while telling me the difference between (in my own words) philosophic silence and collaborative silence. There are times in life when silence is nothing short of cowardly betrayal. Yes, Iya Onisuuru did get angry a few times especially when confronted by cases of blatant injustice and evil.

Thank you, Mother, for being such an extraordinary woman in so many ways. Though never literate, you taught me the alphabet of the language of life. Though never wealthy, you blessed my life with a richness beyond all material possessions. Many, many times you went hungry so that your children could have something to eat. OMO ERIN NI I JOGUN OLA: that sole presentable wrapper at the bottom of your box 56 years ago has bequeathed a wardrobe of countless garments. Your loom rests against the wall, waiting, waiting, for the fertile idiom of your shuttle. The dye-pot is aglow with indigo legends . . .

Alapasa eo Owner of the rich apasa

Olobiri eye Owner of the celebrated obiri

A so ‘u d’eu asiko One who turns raw cotton into fanciful garments

A maso teere s’eso ofi One who beautifies the loom with a strip of fabric

Omo alakeke ko jo titi Owner of the spindle which danced so long

Ko gbagbe ulu ou re It forgot the drum of the cotton

Sun un re o.

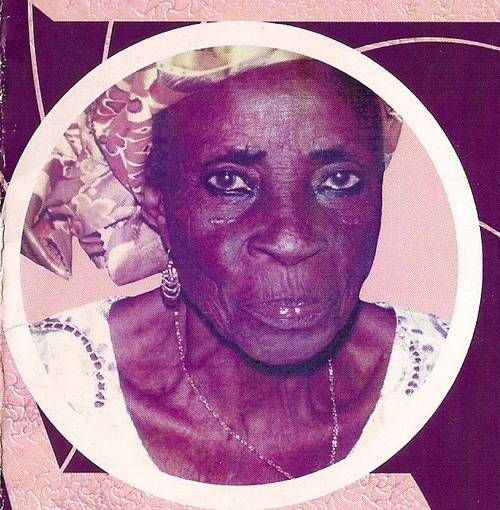

*A Farewell Tribute to the author’s mother, Yeye Fasimia Osundare , who joined the ancestresses on November. 9, 2015, and was committed to Mother Earth on January 8, 2016

Niyi Osundare

December 23, 2015